The Lawn (part of Thomas Jefferson's Academical Village) is a large, terraced grassy court at the historic center of Jefferson's academic community at the University of Virginia. The design shows Jefferson's mastery of Palladian architecture. There is similarity to Palladio's published design for the Villa Trissino (Meledo di Sarego).

Its most famous building is The Rotunda, which sits at the north end of the site, opposite Old Cabell Hall. Interspersed and parallel between them are 10 Pavilions, where faculty reside in the upper two floors and teach on the first, as well as 54 Lawn rooms, where carefully selected undergraduates reside in their final year.

Description[]

The Lawn is used to refer either to the original grounds designed by Thomas Jefferson for the University of Virginia, or specifically to the grassy field around which the original university buildings are arrayed. The Lawn consists of four rows of colonnades on which alternate student rooms and larger buildings. The inner rank of colonnades, facing the central Lawn proper, contains ten Pavilions (which provided both classrooms and housing for the professors who ) and 54 student rooms, while the outer rank, facing outward, contain six Hotels (typically service buildings and dining establishments) and another 54 student rooms. At the head of the colonnades, facing south down the Lawn, is the Rotunda, a one-half scale copy of the Pantheon in brick with white columns, that originally held the University's library.

There are a total of 206 columns surrounding the Lawn: 16 on The Rotunda, 38 on the Pavilions, 152 on the walkways. The columns are of varying orders according to the formality and usage of the space, with Corinthian columns on the exterior of the Rotunda giving way to Doric, Ionic, and Composite orders inside; Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian on each of the pavilions; and a relatively humble Tuscan colonnade along the Lawn walkways.[1]

The neighborhoods of the Lawn include the East Lawn, West Lawn, East Range, and West Range.

West Lawn[]

The West Lawn begins at the north end of the Lawn at Pavilion I, and stretches down the west side of the Lawn, including Pavilion III, Pavilion V, Pavilion VII, and Pavilion IX, along with the odd numbered Lawn rooms 1 through 53. It includes 5 West Lawn, for years the traditional Glee Club room, as well as 7 West Lawn, where the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society was founded, and Pavilion VII, the home of the Colonnade Club. The West Lawn includes a stretch of slightly smaller lawn rooms from , known as "Bachelors' Row."

East Lawn[]

The East Lawn begins at the north end of the Lawn with Pavilion II, and continues down the east side of the Lawn, including Pavilion IV, Pavilion VI, Pavilion VIII, and Pavilion X, along with the even numbered Lawn rooms 2 through 54. It includes Pavilion VIII, which houses the University Guide Service.

West Range[]

The West Range is separated from the West Lawn by a set of gardens that are separated from each other by alleys. Where the West Lawn faces into the Lawn, the West Range faces in the opposite direction, onto McCormick Road. The West Range includes Hotel A, Hotel C (also known as Jefferson Hall, home of the Jefferson Society), and Hotel E, as well as 13 West Range, which was Edgar Allan Poe's room and which the Raven Society maintains in his memory.

East Range[]

The East Range faces the University hospital and is separated from the East Lawn by gardens. Unlike the West Range which is relatively close in elevation to The Lawn, the East Range is at a considerably lower elevation, as it sits along the side of a slope. The East Range includes Hotel B (also known as Washington Hall), Hotel D, and Hotel F (also known as Levering Hall). It also includes the Crackerbox, a two story building behind Hotel F that was once a kitchen and is now student housing.

History[]

Jefferson's design[]

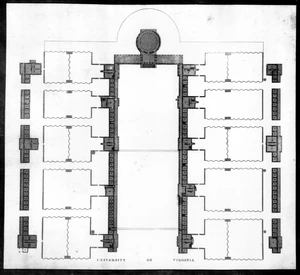

Engraving by Peter Maverick of the plan of the University of Virginia, after Jefferson's drawing, 1826.

Jefferson's design for the Lawn sought to find an alternative to traditional single-building college architecture, such as that he experienced as a student at the College of William and Mary, due to its being "noisy, unhealthy, vulnerable to fires, and affording little privacy."[2] The overall model for the Lawn (the U-shaped plan with a central dome) is similar to, and may have been influenced by, Joseph Jacques Ramée's design for Union College and Benjamin Latrobe's design for a military academy, as well as by the designs of Palladio and by his own house, Monticello. Along the legs of the U, the colonnades provide sheltered, but outdoor, communication between the pavilions and the student rooms, and while everything in the Lawn communicates with the Lawn or the outside world, there is privacy afforded by the walled gardens.[3]

Jefferson separated the buildings of the lawn into 10 units, or Pavilions, to reflect his classification of the branches of learning, and designed the relationship between them and the rest of the Lawn. Each of the ten Pavilions has a unique design, intended to give individual dignity to each branch of study, and the whole was intended to serve as a sort of outdoor classroom for architectural study, as he wrote to William Thornton, architect of the United States Capitol:

What we wish is that these pavilions, as they will show themselves above the dormitories, shall be models of taste and good architecture, and of a variety of appearance, no two alike, so as to serve as specimens for the architectural lecturer. Will you set your imagination to work, and sketch some designs for us, no matter how loosely with the pen, without the trouble of referring to scale or rule, for we want nothing but the outline of the architecture, as the internal must be arranged according to local convenience? A few sketches, such as may not take you a minute, will greatly oblige us.

—Thomas Jefferson, Letter to William Thornton, 1817[4]

Steel engraving, 1831

1856 engraving of the Lawn, looking north

Thornton obliged with designs for two pavilions, one of which was adapted for the design of Pavilion VII, the first to be built. Jefferson also solicited designs from Benjamin Latrobe, who had worked with Jefferson on the chambers for the United States House of Representatives. Latrobe responded with a sketch showing the plan of the University, with a domed structure resembling Palladio's Villa Capra "La Rotonda", and sent a second large drawing in October 1817 showing at least five Pavilion elevations, and maybe 10 (while he had promised Jefferson "seven or eight" Pavilions, the actual drawing has been lost).[5] It is believed that Latrobe's drawings were used for the designs of Pavilions III, V, IX and X[6] Further, it is speculated that many of the eastern Pavilions were based on Latrobe's designs, as Jefferson prepared the drawings for all five buildings in a mere three weeks.[7] Throughout the process, Jefferson adapted the designs to fit the site, adjusting the width, specifying the entablature, and providing the detailed design of the interior of the Rotunda.

The area between the Pavilions and the Ranges was designated as garden space in Thomas Jefferson's original plans. The current design of the gardens is a result of an initiative begun by University president Colgate Darden to return them to something approximating the original Jeffersonian design.[8]

The overall effect of the different portions of the Lawn, the Rotunda, Pavilions, student rooms, and the physical site, is, in the words of Garry Wills, "paradoxical ... regimentation and individual expression ... hierarchical order and relaxed improvising. ... But it is the reconciliation of these apparent irreconcilables that is the genius of the system."[9]

Later changes[]

Following the burning of the Rotunda in 1895, the firm of McKim, Mead, and White and its noted architect Stanford White was hired to rebuild the Rotunda and to create new academic buildings to compensate for the loss of the Rotunda annex. White created three academic buildings, Cocke Hall, Rouss Hall, and Cabell Hall (now Old Cabell Hall) at the base of the Lawn, enclosing the southern view which had previously been open to the Blue Ridge Mountains. The creation of this building group enclosed the Lawn and set its dimensions permanently; subsequent development of the University has happened outside of the boundaries of the Academical Village.[10]

Uses[]

Student rooms on the East Lawn

Graduation exercises at the University of Virginia are held on the Lawn every May, and it is considered one of the institution's major traditions.

Being chosen for residence on the Lawn is one of the University's highest honors and is very prestigious. All undergraduate students who will graduate at the end of their year of residency are eligible to apply to live in one of the 47, out of 54 rooms open to the general student body. Applications – which vary from year to year, but generally include a résumé, personal statement and responses to several questions – are reviewed by a reading committee and the top vote-getters are offered Lawn residency, with several alternates also given notice of potential residency. Five of the remaining seven rooms are "endowed" by organizations on Grounds: the Jefferson Literary and Debating Society (room 7; founded there on July 14, 1825),[11] Trigon Engineering Society (room 17; founded on November 3, 1924), Residence Staff (room 26), the Honor Committee (room 37) and the Kappa Sigma fraternity (room 46; founded there on December 10, 1869).[12] These groups have their own selection process for choosing who will live in their Lawn room although the Dean of Students renders final approval. The Gus Blagden "Good Guy" room (15) resident is chosen from a host of nominees and does not necessarily belong to any particular group. Residency in the John K. Crispell memorial pre-med room (1) is usually granted to an outstanding pre-med student from among the group of 47 offered regular Lawn residency.

Residence in the pavilions is also desirable. However, only nine of the pavilions have faculty residents, as Pavilion VII is the Colonnade Club. The University's Board of Visitors has final approval over which faculty members may live in a pavilion. Pavilion residency is typically offered as a three- or five-year contract with the option to renew. Pavilion residents are expected to interact with their younger "Lawnie" neighbors, as Jefferson intended.

The University has recently begun celebrating winter with the "Lighting of the Lawn". Early each December since 2001, some 22,000 small white lightbulbs are draped around the various buildings of the Lawn and lit up at once with great ceremony, immediately following the reading of a student-composed holiday-themed poem. The lights are turned on each nightfall until the end of the semester, usually about two weeks later. Thousands of students turn out for the opening event.

The South Lawn Project[]

Today's view of the Lawn, looking south toward Old Cabell Hall; the East Lawn is to the left.

The Lawn changed considerably as a consequence of the South Lawn Project. The McIntire School of Commerce was moved to a newly renovated Rouss Hall, formerly home of the College's Economics department, leaving Monroe Hall (former home of the McIntire School) to become part of the College of Arts and Sciences. As part of the project, the Lawn was extended via a bridge over Jefferson Park Avenue to the space across and "above" the street. New Cabell Hall will be renovated (though it was originally planned for demolition).[13] The overall project will add over 100,000 square feet (9,290 m2) of classroom and office space.[14]

Originally awarded to modernist New York architecture firm Polshek Partnership,[15] the current architects, Moore Ruble Yudell, have chosen a neoclassicist approach for the project. Criticism has arisen over the allegedly derivative architectural nature of the project. Not only does it ape certain aspects of The Lawn, leading some critics to call it a "theme park,"[16] but it also would utilize a traditional red brick appearance that critics allege that the always-innovating Jefferson – were he alive today – would have dumped as new technologies arose.

This tension, common on college campuses around America and elsewhere, illustrates the broader conundrum of how to expand an architectural icon, taking advantage of modern building techniques and related cost advantages, without being obviously derivative in style. Other critics take the point of view that the neoclassicist approach is more appropriate in the context of the University of Virginia, contrasting the plans to other University projects like the modernist Hereford College and the revivalist Darden School.[17] There has been open feuding over the neoclassical architectural approach ultimately chosen, with both sides writing letters or taking out ad space in the University's student newspaper, the Cavalier Daily.[18]

The University has stated its intention to have the South Lawn Project LEED certified.[19] The South Lawn Project was completed in the fall of 2010.[14]

Notes and references[]

- ↑ Wills, 55–56.

- ↑ Wills, 51.

- ↑ Wills, 49–52.

- ↑ Jefferson, Thomas (1817-05-09). "Letter to William Thornton from Monticello". http://historyofideas.org/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=Jef1Gri.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=18&division=div1.

- ↑ Wills, 91–94.

- ↑ Bruce, I:187.

- ↑ Wills, 102.

- ↑ Dabney, 392.

- ↑ Wills, 17.

- ↑ Bruce, IV: 274–277.

- ↑ Patton, 235.

- ↑ Kappa Sigma (April 1905). Caduceus of Kappa Sigma. pp. 341–343. http://books.google.com/?id=VwETAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA354-IA4&vq=46+east+lawn&dq=%22kappa+sigma%22+46+east+lawn+%22university+of+virginia%22.

- ↑ Kelly, John (2007-08-14). "New Cabell Hall gets new lease on life". A&S Magazine. http://magazine.clas.virginia.edu/x11348.xml.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "South Lawn". University of Virginia Facilities. http://www.fm.virginia.edu/fpc/FeaturedProjects/SouthLawn/SouthLawn.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ Graham, James D. (2002-02-14). "The new New Cabell: Polshek Partnership to tackle south Lawn project". The Hook. http://www.readthehook.com/stories/2002/02/14/theNewNewCabellPolshekPart.html.

- ↑ Stuart, Courteney (2005-06-11). "South Lawn setback: Modernist architects off the job". The Hook. http://www.readthehook.com/stories/2005/06/09/newsSouthLawnSetbackModern.html.

- ↑ Leigh, D. Catesby (2005-10-02). "A Classical Return: South Lawn Project at UVa Requires Traditional Architecture". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Archived from the original on 2005-10-02. http://www.mimsstudios.com/classicalreturn.htm. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- ↑ McNair, Dave (2006-04-20). "Architects scrap over South Lawn Project". The Hook. http://www.readthehook.com/stories/2006/04/20/onarchsouthlawn.aspx.

- ↑ Kelly, John (2007-08-14). "Going green: South Lawn to earn national green building designation.". A&S Magazine. http://magazine.clas.virginia.edu/x11347.xml.

General references[]

- Bruce, Philip Alexander (1921). History of the University of Virginia: The Lengthening Shadow of One Man. New York: Macmillan.

- Dabney, Virginius (1981). Mr. Jefferson's University: A History. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-0904-X. http://repo.lib.virginia.edu:18080/fedora/get/uva-lib:178665/uva-lib-bdef:100/getFullView.

- Patton, John S. (1906). Jefferson, Cabell, and the University of Virginia. New York: Neale Publishing Company. http://books.google.com/?id=KsI3AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA235&vq=edgar+mason&dq=%22jefferson+society%22+cabell+patton.

- Wills, Garry (2002). 0-7922-5560-7 Mr. Jefferson's University. Washington, DC: National Geographic Directions. ISBN 0-7922-6531-9. http://books.google.com/?id=AXfYAAAACAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=editions:ISBN 0-7922-5560-7.

See also[]

- Jeffersonian architecture

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lawn (University of Virginia). |

- The Lawn Tour: The Academical Village

- "100 Years of Life on the Lawn". University of Virginia. http://www.virginia.edu/100yearslawn/index.html. Retrieved 2008-08-29.

- Cocola, Jim. "The Ideological Spaces of the University of Virginia". http://faculty.virginia.edu/villagespaces/essay/. Retrieved 2008-09-09.

- University of Virginia, Pavilions & Hotels, University Avenue & Rugby Road, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 4 photos and 1 measured drawing at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Hotel A, West Range, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 10 measured drawings at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Hotel C, West Range, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 8 measured drawings at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Hotel E, West Range, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 8 measured drawings and 11 data pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Pavilion I, East Lawn, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 12 measured drawings at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Pavilion II, East Lawn, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 6 measured drawings and 31 data pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Pavilion III, West Lawn, University of Virginia Campus, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 10 measured drawings and 45 data pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Pavilion IV, East Lawn, University of Virginia campus, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 10 measured drawings at University of Virginia, Pavilion IV, East Lawn, University of Virginia campus, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Pavilion VI, East Lawn, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 12 measured drawings at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Pavilion VII, West Lawn, University of Virginia Campus, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 5 measured drawings and 6 data pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Pavilion VIII, East Lawn, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 9 measured drawings and 14 data pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Pavilion IX, West Lawn, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 17 measured drawings and 14 data pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

- University of Virginia, Pavilion X, East Lawn, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Charlottesville, VA: 8 measured drawings and 6 data pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |